OF ALL RELIGIOUS RELICS, the reputed burial cloth of Christ held since 1578 in Turin has generated the greatest controversy. Centuries before science cast the issue in a totally new perspective, disputes over the authenticity of the Shroud involved eminent prelates and provoked a minor ecclesiastical power struggle. From its first recorded exhibition in France in 1357, this cloth has been the object of mass veneration, on the one hand, and scorn from a number of learned clerics and freethinkers, on the other. Appearing as it did in an age of unparalleled relic-mongering and forgery and, if genuine, lacking documentation of its whereabouts for 1,300 years, the Shroud would certainly have long ago been consigned to the ranks of spurious relics (along with several other shrouds with similar claims) were it not for the extraordinary image it bears.

Sepia-yellow in color, the apparent frontal and dorsal imprints of a man's body may be discerned on this 4.3 X 1.1-m linen cloth. Stains of a slightly darker carmine or rust color, with the appearance of blood, are seen in areas consistent with the biblical account of the scourging and crucifixion of Christ. The image lacks the sharp outline and vivid color of a painting and is described as "melting away" as the viewer approaches the cloth. Yet the consensus of skeptical opinion up to the 1930s (with a few surviving remnants today) was that the image was indeed a medieval painting of Jesus which had through time taken on the appearance of a truly ancient relic.

Modern technology served as a catalyst to renewed controversy when the Shroud was first photographed, during a rare exhibition in 1898. Black-and-white photography had the fortuitous effect of considerably heightening the contrast of the image, thus bringing out details not readily discernible to the naked eye. Remarkably, its negative image was found to be an altogether more lifelike portrait of the body and, especially, of the face. From the rather grotesque and murky facial imprint visible on the cloth, reversal of light and dark revealed a harmonious and properly proportioned visage. This discovery of course created a sensation in the media, with claims of miraculous intervention and accusations of darkroom hoax.

Photography made another and far more important contribution in making available copies and enlargements of the Shroud image for detailed study by anatomists and art historians. By the time of its next exhibition in 1931, the Shroud had attracted a considerable following among scholars; it was inspected at that time by experts in various fields, and a vastly superior set of photographs was taken (see figs. 1 and 2). The scientific inquiry into this object, whether medieval fraud or "the holiest icon upon the holiest relic" (Stacpoole 1978), had begun, culminating by 1980 in what must be the most intensive and varied scrutiny by scientific means of any archaeological or art object in history.

In a statement which may not be as hyperbolic as it seems, Walsh (1963:8) observed: "The Shroud of Turin is either the most awesome and instructive relic of Jesus Christ in existence... or it is one of the most ingenious, most unbelievably clever, products of the human mind and hand on record. It is one or the other; there is no middle ground." However, as in almost every complex issue, there is indeed a middle ground (albeit rather weak) in this case, but it has not to my knowledge been investigated in other writings on the Shroud. Clearly, every remote possibility of forgery, hoax, accident, or combination thereof must be examined before a firm archaeological/historical judgement on this artifact can be proffered.

Of the three interrelated areas of interest in this relic - authenticity, mechanism of image formation, and religious significance - we shall be concerned here mainly with the first. While high technology and theology contend respectively with the other aspects of the relic, determination of its origin and place in history is an archaeological issue. The cloth is an unprovenanced artifact purporting to be associated with events in recorded history and encoded with considerable information about its past. Direct study and testing of the relic since 1900 have yielded a wealth of data, and in this paper I attempt to review and summarize the major empirical data and other relevant research. Further, and unlike the authors of the most recent broad reviews on Shroud studies (e.g. Wilson 1978, Sox 1981, Schwalbe and Rogers 1982), I address the question of authenticity in historical/archaeological terms.

Authentication of the Shroud differs from that of manuscripts, sculptures, and other materials only in the wide range of data from many disciplines - anatomy, scientific analyses, history, archaeology, art history, exegesis - which has a bearing on the issue. The fact that it is a religious relic associated with supernatural claims is of no consequence here; certainly there is no justification for employing different or stricter criteria than for any other important artifact, except perhaps in according greater consideration to the possibility of forgery. Considerations of the Shroud have frequently been marred by an intense desire to believe and an imprecise use of data among the overzealous and by an insistence on impossible standards of proof among the skeptics. Clearly, authenticity should be judged on criteria no more and no less stringent than those applied in the usual identification of ancient city sites, royal tombs, manuscripts, etc.

|

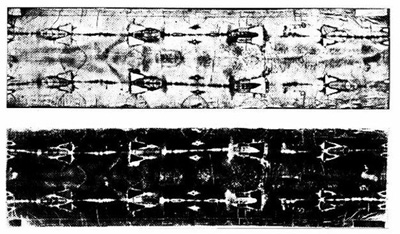

The Shroud of Turin as seen by the naked eye (above, top image) and in photographic negative (above, bottom image). Amidst burn marks, patches, water stains, and creases, the frontal and dorsal images of a male body may be discerned, with apparent blood flows at the wrists, right side (in the positive), head, and feet. Photograph by G. Enrie, 1933; © 1935, 1963 by the Holy Shroud Guild.

|

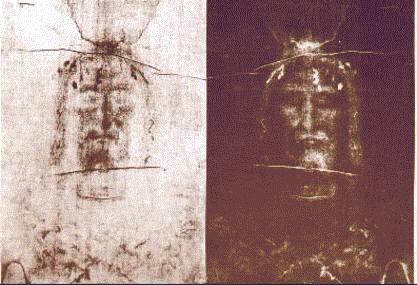

The facial imprint on the Shroud of Turin as it appears to the viewer (above, left) and in photographic negative (above, right). Photograph by G. Enrie, 1933; © 1935, 1963 by the Holy Shroud Guild.

THE BODY IMPRINT

Scientific scrutiny of the Shroud image began in 1900 at the Sorbonne. Under the direction of Yves Delage, professor of comparative anatomy, a study was undertaken of the physiology and pathology of the apparent body imprint and of the possible manner of its formation. The image was found to be anatomically flawless down to minor details: the characteristic features of rigor mortis, wounds, and blood flows provided conclusive evidence to the anatomists that the image was formed by direct or indirect contact with a corpse, not painted onto the cloth or scorched thereon by a hot statue (two of the current theories). On this point all medical opinion since the time of Delage has been unanimous (notably Hynek 1936; Vignon 1939; Moedder 1949; Caselli 1950; La Cava 1953; Sava 1957; Judica-Cordiglia 1961; Barbet 1963 ; Bucklin 1970; Willis, in Wilson 1978; Cameron 1978; Zugibe, in Murphy 1981). This line of evidence is of great importance in the question of authenticity and is briefly reviewed below.

The body was that of an adult male, nude, with beard, mustache, and long hair falling to the shoulders and drawn at the back into a pigtail. Height is estimated at between 5 ft. 9 in. and 5 ft. 11 in. (175-180 cm), weight at 165-180 lb. (75-81 kg), and age at 30 to 45 years. Carleton Coon (quoted in Wilcox 1977:133) describes the man as "of a physical type found in modern times among Sephardic Jews and noble Arabs." Curto (quoted in Sox 1981:70, 131), however, describes the physiognomy as more Iranian than Semitic. The body is well proportioned and muscular, with no observable defects.

Death had occurred several hours before the deposition of the corpse, which was laid out on half of the Shroud, the other half then being drawn over the head to cover the body. It is clear that the cloth was in contact with the body for at least a few hours, but not more than two to three days, assuming that decomposition was progressing at the normal rate. Both frontal and dorsal images have the marks of many small drops of a postmortem serous fluid exuded from the pores. There is, however, no evidence of initial decomposition of the body, no issue of fluids from the orifices, and no decline of rigor mortis leading to flattening of the back and blurred or double imprints.

Rigor mortis is seen in the stiffness of the extremities, the retraction of the thumbs (discussed below), and the distention of the feet. It has frozen an attitude of death while hanging by the arms; the rib cage is abnormally expanded, the large pectoral muscles are in an attitude of extreme inspiration (enlarged and drawn up toward the collarbone and arms), the lower abdomen is distended, and the epigastric hollow is drawn in sharply. The protrusion of the femoral quadriceps and hip muscles is consistent with slow death by hanging, during which the victim must raise his body by exertion of the legs in order to exhale.

The evidence of death in a position of suspension by the arms coupled with the characteristic wounds and blood flows indicate that the individual had been crucified. The rigor mortis position of outstretched arms would have had to be broken in order to cross the hands at the pelvis for burial, and a probable result is seen in the slight dislocation of the right elbow and shoulder. The feet indicate something of their original positioning on the cross, the left being placed on the instep of the right with a single nail impaling both. Apparently there was some flexion of the left knee to achieve this position, leaving the left foot somewhat higher than the right. Two theories, each supported by experimental or wartime observations, contend as regards cause of death: asphyxiation due to muscular spasm, progressive rigidity, and inability to exhale (Barbet, Hynek, Bucklin) or circulatory failure from lowering of blood pressure and pooling of blood in the lower extremities (Moedder, Willis).

Of greatest interest and importance are the wounds. As with the general anatomy of the image, the wounds, blood flows, and the stains themselves appear to forensic pathologists flawless and unfakeable. "Each of the different wounds acted in a characteristic fashion. Each bled in a manner which corresponded to the nature of the injury. The blood followed gravity in every instance" (Bucklin 1961:5). The bloodstains are perfect, bordered pictures of blood clots, with a concentration of red corpuscles around the edge of the clot and a tiny area of serum inside. Also discernible are a number of facial wounds, listed by Willis (cited in Wilson 1978:23) as swelling of both eyebrows, torn right eyelid, large swelling below right eye, swollen nose, bruise on right cheek, swelling in left cheek and left side of chin.

The body is peppered with marks of a severe flogging estimated at between 60 and 120 lashes of a whip with two or three studs at the thong end. Each contusion is about 3.7 cm long, and these are found on both sides of the body from the shoulders to the calves, with only the arms spared. Superimposed on the marks of flogging on the right shoulder and left scapular region are two broad excoriated areas, generally considered to have resulted from friction or pressure from a flat surface, as from carrying the crossbar or writhing on the cross. There are also contusions on both knees and cuts on the left kneecap, as from repeated falls.

The wounds of the crucifixion itself are seen in the blood flows from the wrists and feet. One of the most interesting features of the Shroud is that the nail wounds are in the wrists, not in the palm as traditionally depicted in art. Experimenting with cadavers and amputated arms, Barbet (1953:102-20) demonstrated that nailing at the point indicated on the Shroud image, the so-called space of Destot between the bones of the wrist, allowed the body weight to be supported, where-as the palm would tear away from the nail under a fraction of the body weight. Sava (1957:440) holds that the wristbones and tendons would be severely damaged by nailing and that the Shroud figure was nailed through the wrist end of the forearm, but most medical opinion concurs in siting the nailing at the wrist. Barbet also observed that the median nerve was invariably injured by the nail, causing the thumb to retract into the palm. Neither thumb is visible on the Shroud, their position in the palm presumably being retained by rigor mortis.

The blood flow from the wrists trails down the forearms at two angles, roughly 55° and 65° from the axis of the arm, thus allowing the crucifixion position of the arms to be reconstructed. It is generally agreed that the separate flows from the left wrist and the interrupted streams along the length of the arm are due to slightly different positions assumed by the body on the cross. This seesaw motion is interpreted as necessary simply in order to breathe or as an attempt to relieve the pain in the wrists (the median nerve is also sensory and pain from injuries to it excruciating). A postmortem blood flow with separation of serum is seen around the left wrist and more copiously at the feet, presumably from the removal of the nails.

The pathology described thus far may well have characterized any number of crucifixion victims, since beating, scourging, carrying the crossbar, and nailing were common traits of a Roman execution. The lacerations about the upper bead and the wound in the side are unusual and thus crucial in the identification of the Shroud figure. The exact nature of these wounds, especially whether they were inflicted on a living body and whether they could have been faked, is highly significant. Around the upper scalp and extending to its vertex are at least 30 blood flows from spike punctures. These wounds exhibit the same realism as those of the hand and feet: the bleeding is highly characteristic of scalp wounds with the retraction of torn vessels, the blood meets obstructions as it flows and pools on the forehead and hair, and there appears to be swelling around the points of laceration (though Bucklin [personal communication, 1982] doubts that swelling can be discerned). Several clots have the distinctive characteristics of either venous or arterial blood, as seen in the density, uniformity, or modality of coagulation (Rodante 1982). One writer (Freeland, cited in Sox 1981) questions the highly visible nature of the wounds and clots, as if the Shroud man had been bald or the stains painted over the body image.

Between the fifth and sixth ribs on the right side is an oval puncture about 4.4 X 1.1 cm. Blood has flowed down from this wound and also onto the lower back, indicating a second outflow when the body was moved to a horizontal position. All authorities agree that this wound was inflicted after death, judging from the small quantity of blood issued, the separation of clot and serum, the lack of swelling, and the deeper color and more viscous consistency of the blood. Stains of a body fluid are intermingled with the blood, and numerous theories have been offered as to its origin: pericardial fluid (Judica, Barbet), fluid from the pleural sac (Moedder), or serous fluid from settled blood in the pleural cavity (Saval, Bucklin).

So convincing was the realism of these wounds and their association with the biblical accounts that Delage, an agnostic, declared them "a bundle of imposing probabilities" and concluded that the Shroud figure was indeed Christ. His assistant, Vignon (1937), declared the Shroud's identification to be "as sure as a photograph or set of fingerprints." Ironically, the most vehement opposition was to come from two of Europe's most learned clerics.

THE HISTORY OF THE SHROUD

While medical studies of the body image were providing strong evidence for genuineness, inquiries into the Shroud's history showed its case to be extremely weak. In 1900, the distinguished scholar Canon Ulisse Chevalier published a series of historical documents shedding light on the early years of the Shroud in France and casting seemingly insurmountable doubts on its authenticity. An English Jesuit, Herbert Thurston, condemned the relic in a persuasive and powerful style "that muted and almost stifled the controversy in the English-speaking world" (Walsh 1963:69).

With rivals at Besançon, Cadouin, Champiegne, and elsewhere, this purported "Shroud of Christ" appeared in 1353 in Lirey, France, under mysterious circumstances and with no documentation whatever. It immediately began to draw large numbers of pilgrims to a modest wooden church founded by the Shroud's owner and tended by six clergy but in financial difficulties. Its exhibition was condemned by the resident bishop, Henri de Poitiers. His successor, Pierre d'Arcis, compiled a memorandum in 1389 urging the pope to prohibit further exhibitions of the relic because its fraudulent nature had been discovered by de Poitiers and an unnamed artist had confessed to painting the image. To d'Arcis, the absence of historical reference was equally damning; he considered it "quite unlikely that the Holy Evangelists would have omitted to record an imprint on Christ's burial linens, or that the fact should have remained hidden until the present time" (quoted in Thurston 1903). In all the recorded veneration of countless relics down to the 13th century, there had been no mention of Christ's shroud's bearing an imprint of his body. This silence of history together with the suspicious circumstances of the Shroud's appearance and the confession of the artist seemed sufficient to settle the matter. Thurston concluded confidently, ''The case is here so strong that. . . . the probability of an error in the verdict of history must be accounted, it seems to me, as almost infinitesimal." However, this historical argumentum ex silencio must be considered as an open verdict, as we shall see.

In 1203, a French soldier with the Crusaders camped in Constantinople (who were responsible for the sack of the city the following year) noted that a church there exhibited every Friday the cloth in which Christ was buried, and "his figure could be plainly seen there" (de Clari 1936:112). It is likely that this cloth and the Turin Shroud are the same, especially in view of the pollen evidence (discussed below) and the fact that these are the only known "Shrouds of Christ" with a body imprint. It now seems virtually certain that the Turin Shroud was among the spoils of the Crusades, along with many other relics looted from churches and monasteries in the East and brought back to Europe. Another shroud, now at Cadouin, was found by the Crusaders at Antioch in 1098, brought back to France, and venerated down to the present. (Unfortunately for its cult, the Cadouin Shroud was discovered to have ornamental bands in Kufic carrying 11th-century Moslem prayers [Francez 1935:7).) Wilson (1978:200-215) argues that the Turin Shroud was held and secretly worshipped by the Knights Templars between 1204 and 1314, passing later into history in the possession of a knight with the same name as the earlier Templar master of Normandy (Geoffrey de Charny). Others (e.g., Rinaldi 1972:18) identify the Turin Shroud with the "Burial Sheet of the Redeemer" brought to Besançon from Constantinople, according to unsubstantiated tradition, by a Crusader captain in 1207.

The enigma of the Shroud's history prior to the Crusades will probably never be resolved, but certain points of departure for hypothesis can be established. Pollen samples taken from it reveal that it has been in Turkey and Palestine, and the medical evidence seems to place it in the era of crucifixion. These data strongly suggest that the Shroud is a relic from the early church period. Whether forgery, accident, or genuine, however, the cloth has escaped the gaze of history through a long period in which a relic purporting to be Christ's burial linen and actually bearing his image would have attracted enormous attention and pilgrimage. Whereas other important relics acquired by the Byzantine capital were received with much fanfare and ample recording, there is no mention of when or from what quarter this shroud was obtained. It first appears in the lists of relics held at Constantinople in 1093 as "the linens found in the tomb after the resurrection."

Of the many relics which "came to light'' during the first great cult of relics in the 4th century, there is no mention of a shroud. However, history is not totally silent on the possible preservation of Christ's burial cloth. In a pilgrim's account dated ca. 570 there occurs a reference to "the cloth which was over the head of Jesus" kept in a cave convent on the Jordan River. In 670, another pilgrim described having seen the 8-ft.-long shroud of Christ exhibited in a church in Jerusalem (cited in Green 1969). Earlier references to the preservation of the burial linens are more legendary. A passage in the apocryphal 2d-century "Gospel of the Hebrews" relating that Jesus gave his shroud to the servant of the priest and a statement by St. Nino of the 4th century that the burial linen was held first by Pilate's wife and then by Luke the evangelist, "who put it in a place known only to himself.''

It is of course impossible to establish whether any of these early references actually describe the Turin Shroud, and we may conclude only that it was possibly lost or kept in relative obscurity during the early centuries, eventually being taken to Constantinople. If genuine, the most difficult time for which to construct a plausible scenario is the earliest period. How might such an important relic of Christ's burial have been preserved by persons and in circumstances unknown to the early church at large? And, whether genuine or forged, what is to account for the 700 to 1,000 years during which the image on the cloth is not mentioned?

The actual shroud of Christ may well have been kept in obscurity by 1st-century Christians, perhaps for political reasons and/or out of aversion to an "unclean" object of the dead. By A.D. 66 the Judaeo-Christians had migrated east of the Jordan, and thereafter little is known of them apart from their increasing isolation from the early church and their heretical tendencies. If the Shroud had been taken from Jerusalem by this group, its obscurity in the early centuries would be understandable. Justin Martyr, writing in mid-2d century, observed that Christians who still kept the practices of orthodox Judaism were a rarity regarded with much suspicion.

Other factors which may have played a role in the Shroud's early history and absence of documentation are (1) a very gradual emergence of a visible image on the cloth, (2) folding or wrapping of the cloth so that none or only a portion of the image was visible, and (3) storage, oblivion, and re-discovery of the relic. In times of prosperity as in turmoil and persecution, valued relics were customarily placed in various parts of church structures, homes, and catacombs; it often happened that these objects were forgotten, only coming to light in later construction or warfare. The looting of Edessa (Urfa, Turkey) by 12th-century Turkish Moslems, for example, yielded "many treasures hidden in secret places, foundations, roofs from the earliest times of the fathers and elders. . . . of which the citizens knew nothing" (Segal 1970:253). Similarly, it was not uncommon for manuscripts, works of art, and relics kept in monasteries gradually to drift out of the collective memory; the most notable example is the Codex Sinaiticus, which reposed in a Sinai monastery for over 1,000 years, its importance totally unknown to its keepers.

Wilson (1978:109-93) has offered an elaborate and ingenious identification of the Shroud, folded four times to show only the face, with the Mandylion, a cloth said to have received the miraculous imprint of Christ's face and to have been taken to Edessa in ca. A.D. 40 by the disciple Thaddeus. This semilegendary account of the "Image of Edessa" describes it as having been hidden in a wall during a persecution in A.D. 57 and forgotten until its discovery during a siege of the city ca. 525. The history of the Mandylion is well documented thereafter; it was held at Edessa until 944 and then at Constantinople until its disappearance in 1204. There are, however, numerous problems with a Shroud/Mandylion link (Cameron 1980), notably the difference in size, separate mention on relic lists, and the silence on its eventual "revelation" as a burial cloth.

The tradition of the miraculous imprint of Christ's face developed first in the Byzantine empire. Gibbon (1776-78: chap. 49) records that "before the end of the sixth century, these images made without hands were propagated in the camps and cities of the Eastern empire." In the 7th and 8th centuries in the West arises a similar tradition, that of Veronica, who wiped the brow of Christ with her veil and found a facial imprint remaining. It is quite possible that these traditions have an ultimate basis in the Shroud and its figure, transformed into an image of the living Christ to accord with early Byzantine iconographic conventions. On the other hand, the flourishing of these traditions represents a most likely impetus and context for a forged burial cloth with body imprint.

In sum, although the Shroud's history prior to 1353 is a matter of much rich conjecture and little firm evidence, there are numerous possible avenues by which the Shroud could have come down to us from the Jerusalem of A.D. 30. Genuine or forged, the absence of references to it in the 1st millennium is equally enigmatic. It must be admitted, however, that even if the Shroud's history could be extended back to the early Byzantine era, the case for its authenticity would not be significantly improved.

THE SHROUD AND THE BIBLICAL RECORD

The fact that the Shroud is not easily harmonized with the Gospel accounts has been taken as evidence both for and against authenticity. A number of biblical scholars (discussed in Bulst 1957 and O'Rahilley 1941) have rejected the Shroud because of a perceived conflict on two points: the washing of the body and the type of linen cloths used in wrapping it. Robinson (1978:69), on the other hand, suggests that "no forger starting, as he inevitably would, from the Gospel narratives, and especially that of the fourth, would have created the Shroud we have." The Shroud could of course be genuine and not necessarily agree in every detail with the biblical account: it could also have been forged by persons who were close to the early burial traditions and therefore based their work on a better understanding of the Johannine Gospel account than is possible today.

The wounds seen in the Shroud image correspond perfectly with those of Christ recorded in the Gospel accounts: beating with fists and blow to the face with a club, flogging, "crown of thorns," nailing in hands (Aramaic yad, including wrists and base of forearm) and feet, lance thrust to the side (the right side, according to tradition) after death, issue of "blood and water" from the side wound, legs unbroken, McNair (1978:23) contends that such an exact concordance could hardly be coincidental: "it seems to me otiose, if not ridiculous, to spend time arguing . . . about the identity of the man represented in the Turin Shroud. Whether genuine or fake, the representation is obviously Jesus Christ."

The apparent bloodstains on the Shroud conflict with the long-established tradition in biblical exegesis that Christ's body was washed before burial, which was carried out "following the Jewish burial custom" (John 19:40). The phrase, however, refers directly to the deposition of the body in a linen cloth together with spices. All of the Gospels convey the information that Christ's burial was hasty and incomplete because of the approaching Sabbath. In the earlier accounts of Mark and Luke, the women are said to be returning on Sunday morning to anoint the body with ointments prepared over the Sabbath, when washing a body for burial was effectively forbidden by the ritual proscription of moving or lifting a corpse.

Greater difficulties are encountered in John's descriptions of the burial linens. The synoptic Gospels record that the body was wrapped or folded in a fine linen sindon or sheet. Although the traditional idea is that this sheet was wound around the body, there is no difficulty in reconciling it with the Shroud. John (20:5-8) describes the body as "bound" with othonia, a word of uncertain meaning generally taken as "cloth" or "cloths.'' In the empty tomb he relates seeing "the othonia lying there, but the napkin (soudarion) which had been over the head not lying with the othonia but folded [or rolled up] in a place by itself." To elucidate this passage, almost as many theories as there are possibilities have been put forward. One which would exclude the Shroud is that the linen sheet was cut up into bands to wrap around the corpse, but most exegetes reject this notion. The fact that Luke describes the body as wrapped in a sindon and then relates that the othonia were seen in the empty tomb is taken by some as an equation of the two, by others as a distinction. Most commentators identify the Shroud with the sindon and offer one of the following interpretations: (1) The othonia is the Shroud, the soudarion is a chin band tied around the head to hold up the lower jaw, and the hands and feet were bound with linen strips. In the account of Lazarus, a soudarion is mentioned "around his face," and his hands and feet are bound with keiriai (twisted rushes). Three-dimensional projections of the Shroud face have indicated a retraction of beard and hair where a chin band would have been tied. The Greek soudarion is clearly a kerchief or napkin. (2) The soudarion is the Shroud, and the othonia are bands used to tie up the body. In the vernacular Aramaic, soudara included larger cloths, and the phrases "over his head" and "rolled up in a place by itself" suggest an item more substantial than a mere kerchief.

Clearly, the Shroud as a ''fifth gospel" is difficult to harmonize with the others. Although it can be worked into the biblical accounts of the burial linen, no evidence for its authenticity can be gleaned therefrom. On the other hand, the exact correspondence of the wounds of Christ with those of the Shroud man is of supreme importance; if genuine, the Shroud would provide a most extraordinary archaeological reflection of the crucifixion accounts rendered by the evangelists. But upon this ultimate question, the verdict of history and exegesis must be recorded as open.

SCIENTIFIC ANALYSES

Direct examination of the Shroud by scientific means began in 1969-73 with the appointment of an 11-member Turin Commission (1976) to advise on the preservation of the relic and on specific testing which might be undertaken. Five of its members were scientists, and preliminary studies of samples of the cloth were conducted by them in 1973. A much more detailed examination of the Shroud was carried out by a group of American scientists in 1978-81 as the Shroud of Turin Research Project (Culliton 1978, Bortin 1980, Stevenson and Habermas 1981, Schwalbe and Rogers 1982).

Samples of pollen collected from the Shroud by commission member Frei (1978) yielded identifications of 49 species of plants, representative of specific phytogeographical regions. In addition to 16 species of plants found in northern Europe, Frei identified 13 species of halophyte and desert plants "very characteristic of or exclusive to the Negev and Dead Sea area." A further 20 plant types were assigned to the Anatolian steppes, particularly the region of southwestern Turkey-northern Syria, and the Istanbul area. Frei concluded that the Shroud must have been exposed to air in the past in Palestine, Turkey, and Europe. Suggestions that the Shroud pollen derives from long-distance wind-borne deposits or from dust from the Crusaders' boots do not merit serious discussion.

The cloth itself has been described (Raes 1976) as a three-to-one herringbone twill, a common weave in antiquity but generally used in silks of the first centuries A.D. rather than linen. The thread was hand-spun and hand-loomed; after ca. 1200, most European thread was spun on the wheel. Minute traces of cotton fibers were discovered, an indication that the Shroud was woven on a loom also used for weaving cotton. (The use of equipment for working both cotton and linen would have been permitted by the ancient Jewish ritual code whereas wool and linen would have been worked on different looms to avoid the prohibited "mixing of kinds.") The cotton was of the Asian Gossypum herbaceum, and some commentators have construed its presence as conclusive evidence of a Middle Eastern origin. While not common in Europe until much later, cotton was being woven in Spain as early as the 8th century and in Holland by the 12th.

The Turin Commission conducted a series of tests aimed at clarifying the nature of the image. Thread samples were removed from the "blood" and image areas for laboratory investigation. Conventional and electron microscopic examination revealed an absence of heterogeneous coloring material or pigment. The image and "blood" stains were reported to have penetrated only the top fibrils; there had been no capillary action, and no material was caught in the crevices between threads. Both paint and blood seemed to be ruled out, and magnification up to 50,000 times showed the image to consist of fine yellow-red granules seemingly forming part of the fibers themselves and defying identification. Finally, standard forensic tests for haematic residues of blood yielded negative results.

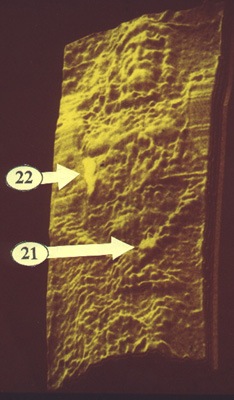

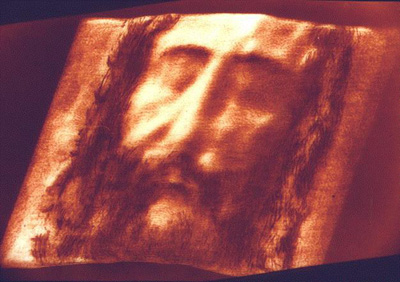

The Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) formed around a nucleus of scientists studying the Shroud by means of computer enhancement and image analysis. Jackson et al. (1977) scanned the image with a microdensitometer to record lightness variations in the image intensity and found a correlation with probable cloth-to-body distance, assuming that the Shroud was draped loosely over the corpse. They concluded that the image contains three-dimensional information, and confirmation was obtained by the use of a VP-8 Image Analyzer to convert shades of image intensity into vertical relief. Unlike ordinary photographs or paintings, the Shroud image converted into an undistorted three-dimensional figure, a phenomenon which suggested that the image-forming process acted uniformly through space over the body, front and back, and did not depend on contact of cloth with body at every point. Computer analysis (Tamburelli 1981) of the body image also revealed that it was formed nondirectionally, whereas the scourge marks exhibited a radiation from two centers to the left and right of the body, the former being somewhat higher than the latter. Enlargements of the scourge marks revealed an extraordinary detail consisting of minute scratches.

The Shroud face is also highly detailed, and the relief figure constructed therefrom had an extraordinary clarity and lifelike appearance. Retraction of the hair and beard where a chin band might have been ties has been noted. Flat, button-like objects interpreted as coins appear on both eyes; the protuberances stand out prominently when processed by isodensity enhancement (Stevenson and Habermas 1981:fig.17). Independently of STURP, another researcher (Filas 1980), working with third-generation enlargements of the 1931 photographs, noted the presence of a design over the right eye, apparently containing the letters UCAI. Filter photographs and enhancements done by STURP also show UC and AI shapes, but somewhat askew (Weaver 1980:753). Whanger (quoted in a United Press International report, April 8, 1982) found exact agreement between the shape and motif of a coin of Roman Palestine and the image over the right eye, when superimposed in polarized light. There is, however, no general agreement on the inscription or on the identification of the protuberances as coins,

The "blood" areas were the subject of special attention from STURP, employing analytical methods of much greater sensitivity than those used by the Turin Commission. Even during cursory inspection, however, it was discovered that, contrary to the Commission's findings, the stains do penetrate to the reverse side of the cloth. Color photomicroscopy (Pellicori and Evans 1981:41) showed the stains to consist of red-orange amorphous encrustations caught in the fibrils and in the crevices. Unlike body image areas, the "blood" regions exhibit the capillary and meniscus characteristics of viscous liquids, viz., penetration, matting, and cementing of the fibers-a phenomenon consistent with blood, paint, or other staining agents. Ultraviolet fluorescence photographs (Gilbert and Gilbert 1980) revealed a pale aura around the stains at the wrist, side wound, and feet, with a fluorescence similar to that of serum, X-ray fluorescence measurements (Morris, Schwalbe, and London 1980) showed significant concentrations of iron only in the blood areas. Both transmission and reflection spectroscopy yielded an absorption pattern characteristic of hemoglobin, and chemical conversion of the suspected heme to a porphyrin was accomplished (Heller and Adler 1980). Blood constituents other than heme derivatives -protein, bilirubin, and albumin - were also identified chemically (Heller and Adler 1981:87-91). A total of 12 tests confirming the presence of whole blood on the Shroud are described by Heller and Adler (1981:92). Finally, fluorescent antigen-antibody reactions (Bollone, Jorio, and Massaro 1981) indicated that the blood is human blood.

The presence of traces of whole blood must be considered as firmly established, with the probability that the blood is human. It is possible, of course, that an artist or forger worked with blood to touch up a body image obtained by other means. Attempts to ascertain how the image came to be imprinted on the cloth have not yielded definitive results. An impressive array of optical and microscopic examinations was conducted, including most of those used in testing for blood constituents, infrared thermography and radiography, micro-Raman analysis, and examination by ion microprobe and electron scanning microscope (Jumper and Mottern 1980). There was general agreement among researchers on the nature of the image - degradation and/or dehydration of the cellulose in superficial fibers resulting in a faint reflection of light in the visible range (Pellicori 1980). Only the topmost fibrils of each thread are dehydrated, even in the darkest areas of the image, and no significant traces of pigments, dyes, stains, chemicals, or organic or inorganic substances were found in the image. It was thus determined that the image was not painted, printed, or otherwise artificially imposed on the cloth, nor was it the result of any known reaction of the cloth to spices, oils, or biochemicals produced by the body in life or death. STURP concluded that "there are no chemical or physical methods . . . and no combination of physical, chemical, biological or medical circumstances which explain the image adequately" (Joan Janney, quoted in an Associated Press report, October 11, 1981). Two theories currently contend among STURP researchers: a "photolysis effect" (heat or radiation scorch) and a "latent image process" where by the cloth was sensitized by materials absorbed by direct contact with a corpse. Wags were quick to label these "the first Polaroid from Palestine" and "a Christ contact print."

Much publicity has been generated by the assertions of McCrone (1980), a former STURP consultant, that the image is a painting, judging from the microscopic identification of traces of iron oxide and a protein (i.e., possible pigment and binder) in image areas. The STURP analysis of the Shroud's surface yielded much particulate matter of possible artists' pigments such as alizarin, charcoal, and ultramarine, as well as iron, calcium, strontium (possibly from the soaking process for early linen), tiny bits of wire, insect remains, wax droplets, a thread of lady's panty hose, etc. (Wilson 1981). However, this matter was distributed randomly or inconsistently over the cloth and had no relationship to the image, which was found to be substanceless, according to the combined results of photomicroscopy, X-radiography, electron microscopy, chemical analyses, and mass spectrometry. McCrone's claims have been convincingly refuted in several STURP technical reports (Pellicori and Evans 1980:42; Pellicori 1980:1918; Heller and Adler 1981:91-94; Schwalbe and Rogers 1982:11-24). The results of previous work by the Italian commission also run totally counter to those claims (Filogamo and Zina 1976:35-37; Brandone and Borroni 1978:205-14; Frei 1982:5). Undaunted, McCrone (personal communication, 1982) continues to stake his reputation on the interpretation of the Shroud image as "an easel painting . . . as a very dilute water color in a tempera medium."

More promising far future research was the identification by micro-analyst Giovanni Riggi of a substance chemically resembling natron, a powder used in ancient Egypt to dehydrate the corpse prior to embalming. An accelerated dehydration process producing a form of Volckringer (1942) print similar to those left by plants pressed in paper is a possibility now under investigation. While further research may shed new light on the origins of the image, the possibility must be recognized that the precise mechanism of image formation may never be known. Scientific testing of the Shroud has not, however, reached a dead end; autoradiography of the entire cloth, thread-by-thread microscopic search, a complete vacuuming of the cloth for pollen and other particles, and of course C14 dating have been suggested.

Proposals for radiocarbon dating of samples from the Shroud are still under consideration by the Catholic church, although approval has been given in principle. The result eventually obtained will undoubtedly have an enormous and, I would submit, unwarranted impact on the general view of the Shroud's authenticity. A C14 age of 2,000 years would not appreciably tilt the scales toward genuineness, as only the cloth, not the image, would be so dated. A more recent date of whatever magnitude would also fail to settle the matter in view of the many possibilities of exchange and contamination over the centuries (variations in ambient atmosphere, boiling in oil and water, exposure to smoke and fire, contact with other organic materials) and the still unknown conditions of image formation, which affected the very cellulose of the linen. The antiquity of the Shroud can, however, be established from archaeological data now available, employing criteria commonly accepted for the dating of manuscripts, ceramics, and stone and metal artifacts not subjected to radiometric measurements.

The fact that the exact manner of image formation is not and may never be known does not pose a serious obstacle to establishing the Shroud's authenticity. The absence of a satisfactory explanation of the image formation does not, as Mueller (1982:27) argues rather curiously, rule out natural processes and leave only human artifice or the supernatural. Rather, the information obtained from medical studies and direct scientific testing establishes the framework for the issue: the Shroud was used to enshroud a corpse, and the image is the result of some form of interaction between body and cloth and does not derive from the use of paint, powder, acid, or other materials which could have been used to create an image on cloth. Whatever process gave rise to the image, the necessary conditions may have prevailed accidentally during a forger's attempted use of a corpse to stain the cloth at in an actual burial. It is virtually unimaginable that a forger of any period would have known of a secret "dry" method (as proposed by Nickell 1979) to produce such an image, a method apparently used only once and evasive of the most sophisticated modern means of detection. The evidence certainly points very strongly toward a natural though extremely unusual process, possibly aided by substances placed with the body and linen at the time of contact.

ANTHROPOLOGICAL, ARCHAEOLOGICAL, AND

ART HISTORICAL CONSIDERATIONS

There is evidence that the body once folded in the Shroud was the victim of a Roman crucifixion. Though used as a method of execution by the Persians, the Phoenicians, the Greeks, and other societies of antiquity, crucifixion in the Roman world was distinctive in a number of ways. Flogging invariably preceded execution and was usually carried out as the condemned proceeded to the crucifixion site; the victim was made to carry his own crossbar and was tied or nailed thereto and then hoisted onto a cross; or a T-shaped frame. Evidence in the Shroud image attests to each of these traits, except that the Shroud man was stationary with arms above the head or outstretched during the flogging. Further, both the whip marks and the side wound appear to have been inflicted with Roman implements. Unlike the depictions of medieval artists, the dumbbell shape of the scourge wounds and their occurrence in groups of two or three match exactly the plumbatae (pellets) affixed to each end of the multithonged Roman flagrum (whip), a specimen of which was excavated at Herculaneum. The side wound is an ellipse corresponding exactly to excavated examples of the leaf-shaped point of the lancea (lance) likely to have been used by the militia: it does not match the typical points of the hasta (spear), hasta veliaris (short spear), or pilum (javelin) used by the infantry. The lance thrust to the side of Christ was, according to Origen of the 4th century, administered, following the Roman military custom, sub alas (below the armpits), where the wound of the Shroud image is located.

The wrist-nailing of the Shroud image is highly significant, as it contradicts the entire tradition in Christian art from the first crucifixion and crucifixion scenes of the early 6th century (hardly 200 years after crucifixion was abolished) down to the 17th century, of placing the nails in the palms (McNair 1978:35). The few portrayals thereafter (Van Dyck, Rubens) of nailing in the wrist have been considered influenced by the Shroud or chronological markers for dating it. Similarly, the impaling of both feet with a single nail occurs in art only in the 11th century and after. Again, the Shroud is construed by some as the origin of the trend, by others as influenced by it. The style of nailing of wrist and feet was confirmed as Roman by a recent archaeological discovery. The first human remains with evidence of crucifixion were unearthed by bulldozers at Giv'at ha-Mivtar, near Jerusalem, in 1968. Among the stone ossuaries of 35 persons deceased ca. A.D. 50-70, one marked with the name Johanan held the remains of a young adult male whose heel bones were riveted by a single nail with traces of wood adhering to it (Tzaferis 1970). At the wrist end of the forearm, a scratch mark as if from a nail was identified on the radial bone; parts of the scratch had been worn smooth from "friction, grating and grinding between the radial bone and the nail towards the end of the crucifixion" (Haas 1970:58), a grim confirmation of the seesaw motion deduced by Barbet to have characterized the final agonies of the Shroud man.

In several important respects, however, the Shroud evidence varies from the usual crucifixion and burial practices of 1st-century Palestine. Prior to crucifixion, a wide range of tortures might be inflicted: gouging of the eyes, mutilations, burning of the hair, etc. (Hengel 1977). The choice of torments apparently depended on the inclinations of the execution party and was bounded only by a concern to avoid the premature death of the condemned. The "crown of thorns" devised for Christ and the mocking and beatings appear to derive from the judicially sanctioned subjection of the condemned to the caprice of his guards. The Shroud man, like Christ, was flogged in a stationary position rather than on the way to the execution ground. In deference to strong Jewish feeling against leaving a corpse exposed after sunset, the Roman administration in Palestine allowed the breaking of the legs (crurifragium) to hasten death. John's Gospel (19:32) specifically records that the thieves crucified with Christ had their legs broken in order that the bodies could be taken down before nightfall. The right tibia, left tibia, and fibula of the Johanan remains were also broken, but the legs of the Shroud man were not. There is no historical mention of any other method of hastening death or coup de grace, and indeed crucifixion elsewhere in the empire was mandated to be a slow and agonizing death, usually lasting 24-36 hours. The lance thrust to the side of Christ thus appears as a capricious and unique act by one of the guards.

Again out of consideration for local custom, the Romans allowed the bodies of crucified Jews to be buried in a common pit instead of being left on the cross or thrown on a heap for scavenging animals as was the general practice. Certainly the use of a sheet of fine linen cloth such as the Shroud would indicate a degree of wealth, respect, family ties, or ranking not normally pertaining to common criminals. In general burial practice, the body would have been washed and anointed with oils, and the linen would not have been removed from the body. In other respects, the Shroud does accord with burial customs known or surmised of 1st-century Jews. The account by Maimonides, a 12th-century Jewish scholar at Cordova, parallels what can be constructed from the 4th-century Palestinian Talmud, 2d-century Mishna, and biblical accounts: "After the eyes and mouth are closed, the body is washed; it is then anointed with perfumes and rolled up in a sheet of white linen, in which aromatic spices are placed." The possible presence of a chin band and coins over the eyes has been noted; the failure to wash the body may be explained by the Sabbath prohibition or by the existence of early injunctions, similar to those later incorporated in the medieval codes of Rabbinical law, against washing of the body or cutting of the hair, beard, and fingernails of victims of capital punishment or violent death (Lavoie et al. 1981). Finally, the burial posture of the Shroud figure is seen in a number of skeletons excavated at the ca. 200 B.C.-A.D. 70 cemetery of the Essene sect at Qumran (Wilson 1955:60), which were laid flat, facing upwards, elbows bent and hands crossed over the chest or pelvis. Sox (1981:134), however, sees the position as a reflection of medieval modesty.

The placing of coins or shards over the eyes of the corpse was known among medieval Jews and believed to be an ancient tradition (Bender 1895:101-3) to prevent the eyes from opening before glimpsing the next world; in the pagan tradition, coins were placed on the body as payment to Charon for crossing the River Styx. Recent excavations (Hachlili 1979:34) at Jewish tombs of the 1st century A.D. near Jericho have yielded the first evidence of this practice; two coins (A.D. 41-44) were found inside a skull, undoubtedly having fallen through the eye sockets. On the Shroud, the pattern over the right eye exactly matches the size and shape of some of the cruder coins (leptons) of the procuratorial series in Judea, especially those of Gratus (A.D. 15-26) and Pilate (26-36). The UCAI "inscription" was suggested to be a misspelling of the Greek TIBERIOU KAICAROC ("Tiberius Caesar," A.D. 14-37); in 1981 an unpublished coin bearing the letters IOUCAI was discovered in a collection (F. Filas, news release, September 1, 1981). Although the letter-like shapes on the Shroud are not clear enough to be distinguished with certainty from vagaries of the image and the weave, their location in the correct position on the coin shape when seen in relief would seem to give the inscription a small measure of credibility. One cannot, however, go very far with this evidence, for even if the imprint could be confirmed as a Pilate coin, such coins were circulating for at least several decades after minting and were probably obtainable for a considerable time thereafter, the coins of Pilate having gained a certain notoriety in Judea for their use of pagan symbols (Kanael 1963).

Coon's description, noted above, of the Shroud face as Semitic in appearance is supported by Stewart (cited in Stevenson and Habermas 1081:35), who points out other features of the image which suggest a Middle Eastern origin. The beard, hair parted in the middle and falling to the shoulders, and pigtail indicate that the man was not Greek or Roman. The unbound pigtail has been described as ''perhaps the most strikingly Jewish feature" of the Shroud (Wilson 1978:54) and has been shown to have been a very common hairstyle for Jewish men in antiquity. The estimated height of the Shroud man at around 175-180 cm corresponds with the average height (178 cm) of adult male skeletons excavated in the 1st-century cemetery near Jerusalem (Haas 1970) and with the ideal male height of 4 ells (176 cm) according to an interpretation of the Talmud (Kraus 1910-11).

Some of the earliest representations of Christ from the 2d to 4th centuries portray him as youthful, clean-shaven, and Greco-Roman; others depict a bearded, Semitic face much more akin to that of the Shroud. Beginning in the 6th century, the face of Christ in Byzantine art became highly conventionalized, with a certain resemblance to the Shroud figure. Vignon (1939) noted 20 peculiarities in the Shroud face (e.g., a transverse streak across the forehead, a V shape at the bridge of the nose, a fork in the beard, etc.) that are common in Byzantine iconography. He suggested that the Shroud might have been the source of this artistic tradition. Whanger and Whanger (n.d.), using a system of polarized light to superimpose images, found 46 points of congruence between details of the Shroud face and the face of Christ in a 6th-century Mt. Sinai mosaic and 63 points of agreement between the Shroud face and the face of Christ on a 7th-century Byzantine coin. In other respects, however, the Shroud image differs markedly from Byzantine art of the early centuries in revealing a dead Christ, covered with wounds and blood, nude, lacking any indication of majesty or divinity. The crucifixes and crucifixion scenes of the 5th to 8th centuries invariably show a nonsuffering, glorified Christ, eyes open, clad in a tunic, with no bleeding or signs of physical agony. Again, the evidence indicates very strongly that the Shroud image does not derive from the art of this or any era, but may be the source of certain features.

In summary, the evidence from anthropology, archaeology, and art history corroborates in a compelling manner that of medical and scientific analyses. It should now be considered well-established that the Shroud is indeed an archaeological document of crucifixion - a conclusion reached by STURP and most serious students of the Shroud since the 1930s. Attempts to interpret it as a painting (McCrone), a wood-block print (Curto 1976), a bas-relief rubbing (Nickell 1979), a scorch from a hot statue (Papini 1982), or a colored "clay press'' (Gabrielli 1976) are untenable, derive from consideration of only a small portion of the evidence, ignore the vast array of data to the contrary, and need not be discussed further. The confirmation by archaeology of numerous details found in the image and of hypotheses deduced therefrom - nailing of the wrist, single nailing of both feet together, seesaw motion on the cross, coins on the eyes, burial posture, and Middle Eastern origin, even the UCAI "misspelling" - give the Shroud an undeniable ring of authenticity as an archaeological object.

The pollen, the Semitic appearance of the figure, and other anthropological evidence combine to indicate an origin of the Shroud in Palestine or possibly Asia Minor; the pathological data coupled with the evidence of Roman implements and style allow it to be assigned with confidence to the period of Roman crucifixion, thus from the Roman conquest of Turkey and Palestine in 133-66 B.C. to Constantine's banning of this form of execution ca. A.D. 315. The "obvious" representation of Christ in the image further narrows the dating of the Shroud to A.D. 30-315. On this final point of identity we arrive at the "crux" of the issue, for there were thousands of crucifixions during this period in Palestine and Asia Minor.

FORGERY/ACCIDENT HYPOTHESES

The identification of the Shroud figure may be approached by testing the uniqueness of the set of traits it shares with the historical description of the death of Christ. That is, the question may be posed whether these shared details can be established to a reasonable degree as historically specific, in the same manner that, for example, the singular characteristics of the tomb of Tutankhamen or the Shang-dynasty kings mentioned in oracle texts allow a definite identification. Such an archaeological/historical identification may be initiated by endeavoring to generate alternative hypotheses, derived from the known historical context, which might account for the configuration of features characterizing the Shroud. Calculations of cumulative probabilities (e.g., Donovan 1980; Stevenson and Habermas 1981:124-29) based on mere historical guesswork (legs not broken: 1 chance in 3; lance thrust to side: 1 in 27; etc.) are of no scientific validity whatever.

In order to be as definitive as possible, we shall examine a wide range of scenarios - some little more credible in ancient history than the notion that Hitler is alive in Brazil is in the present. And yet, any conceivable scenario which could be successfully superimposed on the Shroud's particular pattern of data would have to be taken seriously. In considering the Shroud as a possible forgery, an unwarranted emphasis on intentionality creeps into the discussion. Between deliberate hoax and true relic are various shades of accident, mistaken identity, excessive reverence for an inspirational "visual aid," and/or exaggerated claims. The ultimately important question is, of course, not how this image on cloth came to be taken as Christ's, but how it acquired such an extraordinary accuracy in the details of Christ's historically known life and anthropologically known times.

Painting

The interpretation of the Shroud as a painting by an unknown medieval artist emerged from its suspicious history as highly likely and has persisted with unusual stubbornness down to the present. Its prominence as the main forgery theory is such that virtually all commentators expend great effort in disproving it, believing the authenticity of the relic to be established thereby. The notion has indeed been disproved so thoroughly and absolutely that it should be permanently buried. I shall simply list yet again the numerous items of evidence, many of which would be sufficient singly to establish that the image is not a medieval painting, rubbing, scorch, or other work of art: anatomical detail, realism of the wounds, presence of blood, absence of pigment or binder, reversal of light and dark, diffuseness of the image at close range, three-dimensional information, absence of outline or shading, lack of directionality in the colored areas, lack of change in color from light to dark tones, color not affected by heat or water, detail and twin radiation of scourge marks, nailing of wrists, single nailing of both feet together, characteristic wounds of the Roman flagrum and lancea, Oriental cap rather than Western circlet crown, accuracy in Semitic appearance and Jewish burial posture, pollen from Turkey and Palestine, difficulty in reconciling the Shroud with biblical accounts, nudity of the figure. Each of these features could be explained by invoking extraordinary circumstance, e.g., absence of pigment due to the use of a thin solution and frequent washings of the relic, real blood used by the artist, pathological exactitude from the artist's genius, scourge marks and wrist nailing from intuition, a cloth of Middle Eastern origin, etc. Clearly, however, the cumulative effect is to place the painting hypothesis somewhat lower in credibility than notions of the Marlowe authorship of Shakespeare's plays or an Egyptian influence on the Mayas.

Unknown Crucifixion Victim

Guilty of McNair's charge of otiosity, a number of commentators, including the STURP team, have suggested that the Shroud could be the gravecloth of a person who suffered injuries in the same manner as Christ. We shall examine here the possibility of such an occurrence without obvious intent to imitate the experiences of Christ. This hypothesis thus hinges on the degree to which features now interpreted as "clearly representing Jesus Christ" should be considered unique.

The major characteristics of the Shroud figure which seem to identify him as Christ are the lacerations of the head and the wound in the side; of lesser importance are the evidence of stationary flogging: and absence of crurifragium. Certainly, the methods of capital punishment did not always follow a rigid procedure; an example is the occasional lifting of prohibitions on the use of the flagrum or crucifixion to punish Roman citizens. Political prisoners in Palestine may well have received harsher penalties than common criminals in the form of more severe flogging and prolonged sufferings on the cross. On the other hand, the bodies of rebels and subversives were not normally released for burial, according to a 6th-century digest of Roman law (Ulpian, cited in Barbet 1963:51). In the Matthew account (28:62-64), the Sanhedrin were clearly unprepared when the request for Christ's body was granted.

The crowning with thorns is described in John's Gospel as a spontaneous and capricious invention of the guards in response to absurd claims of kingship associated with their prisoner. Ricci (1977:67) and others contend that this trait is a singular and identifying mark of Christ; among the recorded tortures of the condemned prior to crucifixion there is no such crowning or spiking of the scalp. It must be allowed, however, that similar injuries might have been sustained by other crucified men, perhaps palace intriguers or leaders of rebellion. An instance is recorded by Philo of a mock crowning in ca. A.D. 40 during a visit of the Jewish King Agrippa to Alexandria; a mock procession was staged with an idiot dressed in ragged royal purple and crowned with the base of a basket. Preexecution tortures might also have caused punctures of the scalp resulting, if credulity is strained, in a pattern similar to an Oriental crown (mitre or cap) of thorns. Therefore, while the parallel between the head wounds of the Shroud man and those of Christ is striking, it is not sufficient of itself to establish the identification.

The postmortem nature of the side wound also exactly parallels the biblical account, and again there is no historical mention of a practice of this or any method of coup de grace during crucifixion, other than the crurifragium in Palestine. Bulst (1957:121) interprets an ambiguous phrase in Quintilian (1st century) as suggesting that piercing the corpse may have preceded its release for burial. However, an exhaustive search by Vignon (1939) and Wuenschel (1953) turned up only one slightly dubious reference to such a practice: the martyrs Marcellus and Marcellinus were dispatched with a spear during their crucifixion ca. 290 because their constant praising of God annoyed the sentries. In this instance, as in that of Christ, the spearing appears as a spontaneous act by the guards. One might conclude that similar transfixions may have occurred occasionally, were it not for the universal attitude in the early church toward the issuance of blood and water from Christ's side. Christian apologists of the 2d and 3d centuries - a period of frequent crucifixions - believed the flow to be a miracle, Origen, who had witnessed crucifixion, could write: "I know well that neither blood nor water flows from a corpse, but in the case of Jesus it was miraculous." Certainly such a belief could not have prevailed if piercing the corpse sub alas had been other than a very rare happening indeed.

The omission of normal washing and anointing of the body may possibly be explained by the onset of the Sabbath, since ritual differential treatment of execution victims does not seem to have been practiced in 1st-century Palestine. The individual burial and quality of linen suggest that the Shroud man was not a criminal, slave, or rebel. Finally, the lack of decomposition staining of the cloth indicates that, barring highly unusual preserving conditions arresting the normal bodily decay, the Shroud was removed from the corpse after 24-72 hours. It would have been kept in spite of the deep-seated aversion of the Jews (and most peoples of antiquity) to anything which had been in contact with the dead, not to mention bearing the actual stain of a corpse. Eventually, the similarity of its imprint with the body of Christ would have been noticed.

Clearly, this scenario requires the most improbable combination of many fortuitous and highly improbable events. For each detail, an explanation of sorts can be concocted, but that all of them could have been strung together accidentally into a configuration corresponding exactly to the biblical account of Christ's crucifixion is, quite simply, inconceivable. The order present in the Shroud data reveals, just as surely as does the workmanship of an artifact, an intentionality in its composition. If it is not the actual Shroud of Christ, it must be the result of a deliberate attempt to duplicate the experiences of his death and burial.

Early Forgery

The first centuries of Christianity afforded ample possibility and motivation for the forgery of a relic such as the Shroud. A widespread cult of relics developed in the 4th century following the conversion of Constantine and was intensified by the discovery of the "True Cross" during an expedition to Jerusalem of Constantine's mother in 326 and the distribution of shavings of the wood throughout the empire. Similar "discoveries" soon followed, of the nails, lance, crown of thorns, clothing, and other material items from the life of Christ, the apostles, Old Testament figures, saints, and martyrs. As noted above, a Shroud of Christ was claimed by a convent on the Jordan in 570, and cloths believed to bear his facial imprint were current by ca. A.D. 500. Early ecclesiastical writers frequently denounced spurious relics created for reasons of rivalry, reverence, or profit, and relic forgery was especially rife in Egypt and Syria in the 4th century, It may be suggested, then, that forgers obtained the corpse of a crucifixion victim, marked it to resemble Christ, and attempted to imprint an image on cloth, achieving by accident a remarkable result.

The objections to this scenario are manifold and insurmountable. Of greatest importance is the medical interpretation of the head wounds as inflicted on a living body; spiking the scalp of a corpse or marking it with blood could not approach the pathological exactitude of the wounds and blood flows on the Shroud man. Straining credulity, one might escape this difficulty by postulating a collusion between forgers and executioners for preparation of a victim with suitable head wounds. The postmortem side wound presents equal if not greater difficulties: it was inflicted on an upright corpse, resulting in a copious flow of blood and clear fluid (matching the biblical account); a second flow issued when the body was horizontal, not simply laid out but being moved, as indicated by the collection of blood across the small of the back. There can be no doubt that early forgers could not have attained such precision and that it was unnecessary in any case for the simple production of a bloodstained cloth for a gullible public.

There are numerous other difficulties with this hypothesis: (1) The major demand for relics came after the state establishment of Christianity, by which time crucifixion had been abolished. (2) Stains, dyes, oils, or other materials likely to have been used by early forgers in an attempt to imprint the cloth are completely lacking on the Shroud. (3) The victim appears to have been Jewish, with the correct burial posture, chin band tied and eyes covered, yet the legs were not broken as was the practice in Palestine. (4) A successful imprint of Christ's likeness made in this era would have been trumpeted as another great relic "come to light." (5) An image of the nude and unwashed body of Christ would have been considered offensive, lessening or destroying its economic and ceremonial value. Based on the already shaky premise that forgers accidentally and spectacularly succeeded in their task, this hypothesis is hopelessly fraught with difficulties. It can be unequivocally rejected, and with it any possibility that the Shroud is the product of a forgery attempt. As Donald Lynn (quoted in Rinaldi 1979:14) of STURP concluded, "it would be miraculous if it were a forgery."

Imitation of Christ

Finally, the possibility may be considered that the Shroud man was literally a "little Christ" - that, out of fanaticism, extreme asceticism or desire for martyrdom, someone was able to inflict or have inflicted the exact wounds of Christ on his own person. There is ample evidence of asceticism and self-denial carried to extremes in the early monastic- anchorite movements of the late 3d and 4th centuries. Hermits isolated themselves in the deserts, in cave cells, on pillars, there to indulge in all manner of bizarre vilifications of the flesh: wearing of chains for years, self-flagellation, dietary privations, exposure to heat and cold, etc. The above-cited theological writer Origen in his youth committed self-castration; the first monk ascete, Paul of Egypt, was reportedly found dead in his cell: in a kneeling position of prayer.

The 4th-century anchorites of Egypt retained practices of mummification of the dead; the body was wrapped in bandages and the outer surface sometimes painted with a mask or Christian symbols. As this custom fell out of use, the dead were simply wrapped in a winding sheet and carried into the desert, to be buried after three days of wailing. The Shroud might thus be the burial sheet of an unknown but charismatic figure in the early anchorite communities of Egypt or Syria, crucified by followers in a manner exactly imitating that of Christ. The presence of natron on the Shroud takes on a special relevance here, and several other details may be fitted into this hypothesis: the wrist and foot nailing of Roman crucifixion would have been known; the victim might have been "Semitic," the crown of thorns conceived of as a cap, the cloth preserved in the desert conditions; and the areas were rife with relic-mongering.

The hypothesis requires, on the other hand, a virtually impossible double occurrence of freakish events: a self-styled crucifixion and a body imprint by unknown mechanism. There are other difficulties: the matching of the wounds with Roman implements, the Jewish burial customs (most unlikely to have been known), the linen itself (luxurious and urban), and of course the silence of the historical record on the entire proceedings. The coup de grace for this wildest of hypotheses is, appropriately, the lance wound in the side. It would have been well nigh impossible to draw forth intentionally from a corpse a flow of blood and fluid at a single thrust. The presence of pericardial or pleural fluid in sufficient quantity and the exact site, angle, and depth of piercing would have to be carefully determined before such a feat could be performed by a modern surgeon, as Barbet discovered in experiments on corpses.

A similar set of historical circumstances can be cited in attributing the Shroud to a crucified martyr eager to imitate the "Way of the Cross." That early Christians sometimes exhibited a fanatical desire for physical suffering and martyrdom is well documented; it is reflected in the remark of Antonius, 3d-century proconsul of Asia, when confronted with mass confessions and volunteers for martyrdom: "Miserable people, if you are so weary of life, is it not easy to find ropes or precipices?" Hagiographies overflow with accounts of martyrs' showing contempt for the exertions of their torturers, and a situation may be imagined in which the condemned entreated or goaded their guards into "glorifying" them with a crown of spikes and a spear wound in the side,

By the 3d century, linen brandea or "second-class relics" were being created by touching them to the body or blood of a martyr. At the beheading of Bishop Cyprian of Carthage in 258, a linen sheet was spread on the ground to collect his blood, and the body was then carried through the streets in the cloth. Is it possible that the Shroud is a similar relic in linen intended to absorb the blood and holiness of an exceptional martyr who bore all of the wounds of Christ? The answer again must be a definite negative. The scenario posits the concurrence of no fewer than four extremely rare and improbable phenomena - a martyr's crown of thorns, a postmortem side wound, blood and fluid issuing therefrom, and the imprint. If a spear thrust to the corpse on the cross had been a common practice, eventually a repetition of the blood and fluid flow from the wound would have occurred, but to attach this extremely unlikely event to the other wounds and features of the Shroud and to the accident of body imprint, all in total historical obscurity, is clearly to enter the world of fantasy.

It is unnecessary to extend this exploration of extremely farfetched and improbable hypotheses to the limits of the imagination, e.g., to concoct a massive conspiracy such as might be formulated to challenge any historical document or fact. Suffice it to note that even the most preposterous notions - e.g., mass crucifixions conducted during the persecutions to replicate in every detail Christ's sufferings (Gramaglia, in Sox 1981:69) - would founder on many of the Shroud's details and on the accidental image formation. Neither should any consideration be given to the ludicrous suggestions of the "paranormal," that the Shroud man was a stigmatist bearing in exact detail all the wounds of Christ, or that the Shroud is a satanic ploy to focus attention on the dead rather than the spiritual Christ.

CONCLUSIONS

The question of authenticity may be readily divided into two stages: (1) the Shroud as a genuine burial cloth recovered from a grave or removed from a corpse and (2) the Shroud as the gravecloth of Christ. The first stage may be established from direct examination of the object and comparison with relevant data from other disciplines. The second stage relies heavily but not entirely on the historical record and, ironically, at certain points on the silence in that record. In the foregoing discussion, we have reviewed the evidence related to each stage of the authentication process. The final judgement generally depends on whether one in inclined to stress the positive or the negative evidence.

As early as 1902, the basic cleavage of opinion an the Shroud was already apparent. For the anatomists, scrutiny of the image yielded positive evidence that it was the imprint of a corpse bearing wounds exactly corresponding to those described of Christ. For historians, the silence of history and the sudden appearance of the relic in suspicious circumstances constituted an equally convincing negative indication. It has been my contention in this paper that, while the lack of historical documentation and the claimed confession of the artist are difficulties, the evidence from the medical studies must be treated as empirical data of a higher order. The dead body always represents a cold, hard fact, regardless of a lack of witnesses or a freely offered confession of murder. With anatomists and forensic pathologists of the highest caliber in Europe and America (many of whom are also well versed in the history of art) of one mind for 80 years about the image as a body imprint, one is on firm ground in characterizing the Shroud as the real shroud of a real corpse. The direct testing of the last 20 years goes farther in demonstrating that the relic is a genuine gravecloth from antiquity rather than the result of a medieval forger's attempt to imprint the cloth with a smeared corpse. Fleming (1978:64) concurs, with the conclusion that "it is the medical evidence that we are certainly looking at a gruesome document of crucifixion which satisfies me that the Shroud is not medieval in origin."

Current opinion on the Shroud's authenticity ranges generally from "probable" to "proven" for Stage 1 and from "possible" to "probable" for Stage 2. For a variety of reasons, not the least of which is the fact that the object is a religious relic, these opinions seem to err an the side of the cautious, place undue emphasis on the negative evidence, and are often based on an assumption that the identity of the Shroud man is "unprovable." Rather, the second stage of authentication may well be more easily demonstrable than the first, as even the arch-skeptic Schafersman (1982a:41) admits. That is to say, if the Shroud image is truly a body imprint (as the evidence overwhelmingly indicates), and if the wounds seen in the imprint are real (on which point there is little room for doubt), then surely we must conclude that the imprint must be from the body of Christ.